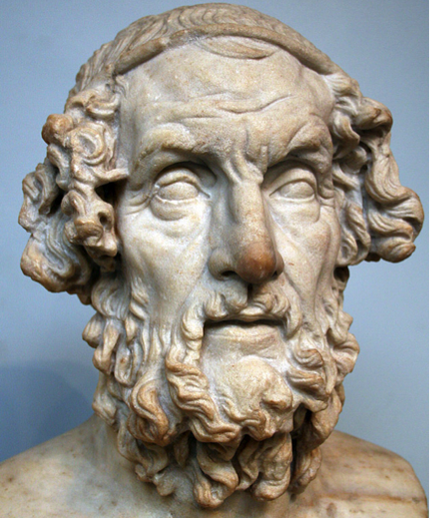

| Homer is the name of the ancient Greek poet (or poets, as we shall see) generally credited with the authorship of the Iliad and Odyssey, the canonical epics about the Trojan War and its aftermath. (Ilion—Latinized to Ilium—is another name for Troy, a Bronze Age city whose ruins are in present-day Turkey; the Odyssey is named for its hero, Odysseus.) Homer’s name has also been attributed to various other poems, particularly a collection of 33 hymns, though modern scholars reject these attributions. But who—if anyone—was the historical Homer? Columbia College gives a useful summary: “Scholars variously consider the Iliad and Odyssey to be the work of a single poet, two different poets, or an ‘evolutionary’ process involving many generations of poets mastering and contributing to the work of their predecessors.” Let’s consider each possibility in turn: |

- There seems to be no evidence, beyond tradition, for the claim that both epics were composed by a single, brilliant poet. According to Britannica, references to “Homer” began appearing in Greek texts in the 7th century BCE, one- to two-hundred years after the man himself was supposed to have lived. These include a hymn attributed to “a blind man who dwells in rugged Chios,” which, together with a similar description of a bard in the Odyssey, helped to establish the tradition that Homer was blind. In addition to Chios (an island in the eastern Aegean Sea), six other Greek settlements have claimed to be Homer’s birthplace; Chios at least was home to the Homerìdai (“Sons of Homer”), a school of bards who specialized in Homeric poetry.

- The claim that the Iliad and Odyssey were composed by two brilliant poets, posthumously conflated as “Homer,” boils down to the substantial differences, in both subject and style, between the two epics: “the Iliad being martial and heroic, the Odyssey picaresque and often fantastic” (Britannica). Poets.org develops this point: “The diction of the two works is markedly different, with The Iliad being reminiscent of a much more formal, theatric style while The Odyssey takes a more novelistic approach and uses language more illustrative of day-to-day speech.” That said, there seems to be no more evidence for two historical authors than for one.

Was “Homer” the culmination of an evolving oral tradition?

According to this (seemingly) comprehensive site, the oldest known complete text of the Iliad was produced in the 10th century CE, and complete texts of the Odyssey survive from several centuries later. By then, printed texts of both poems had been circulating for a thousand years—numerous papyri fragments exist from the 2nd and 3rd centuries BCE. And before they were written down, the poems existed as part of an oral tradition that, according to some scholars, may have stretched as far back as 2000 BCE. Indeed, Homer’s own word for “poet” is aoidos, which means “singer.”

Several times in the Odyssey, aoidoi sing relatively short poems (100 or so verses), for both public and private entertainment, about the deeds of gods and heroes. As Britannica argues, such compositions “must have provided the backbone of the tradition inherited by Homer.” At some point in the history of Greek oral poetry, someone—if not “Homer” then a predecessor—may have invented “a quite different style of poetry, in the shape of a monumental poem that required more than a single hour or evening to sing and could achieve new and far more complex effects.”

Alternatively, epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey may have evolved gradually, over many generations, as aoidoi competed to sing longer and grander tales, until finally a song about the death of Hector had become a “monumental poem” about the pride and wrath, not only of Achilles, but of dozens of legendary heroes (and gods); until individual tales of Odysseus’s wandering—how he outwitted the Cyclops, or survived the Sirens, or visited the underworld—had been stitched together to span decades. Perhaps “Homer” was in fact one of the more skillful masters in this web of influence, the aoidos who became identified with what we now call the Iliad and Odyssey; perhaps the name is simply shorthand for the countless poets who contributed their own verses and variations until finally, centuries after their author is supposed to have lived, the poems were fixed in printed form. I’m not sure there is any more evidence for this alternative to the “great man” theory of Homer, but it strikes me as a likelier possibility.

The techniques used by oral poets to improvise and recall their works is a fascinating topic, though beyond the scope of this post. To learn more about oral poetry, from contemporary cultures as well as ancient Greece, check out these resources:

Several times in the Odyssey, aoidoi sing relatively short poems (100 or so verses), for both public and private entertainment, about the deeds of gods and heroes. As Britannica argues, such compositions “must have provided the backbone of the tradition inherited by Homer.” At some point in the history of Greek oral poetry, someone—if not “Homer” then a predecessor—may have invented “a quite different style of poetry, in the shape of a monumental poem that required more than a single hour or evening to sing and could achieve new and far more complex effects.”

Alternatively, epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey may have evolved gradually, over many generations, as aoidoi competed to sing longer and grander tales, until finally a song about the death of Hector had become a “monumental poem” about the pride and wrath, not only of Achilles, but of dozens of legendary heroes (and gods); until individual tales of Odysseus’s wandering—how he outwitted the Cyclops, or survived the Sirens, or visited the underworld—had been stitched together to span decades. Perhaps “Homer” was in fact one of the more skillful masters in this web of influence, the aoidos who became identified with what we now call the Iliad and Odyssey; perhaps the name is simply shorthand for the countless poets who contributed their own verses and variations until finally, centuries after their author is supposed to have lived, the poems were fixed in printed form. I’m not sure there is any more evidence for this alternative to the “great man” theory of Homer, but it strikes me as a likelier possibility.

The techniques used by oral poets to improvise and recall their works is a fascinating topic, though beyond the scope of this post. To learn more about oral poetry, from contemporary cultures as well as ancient Greece, check out these resources:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed